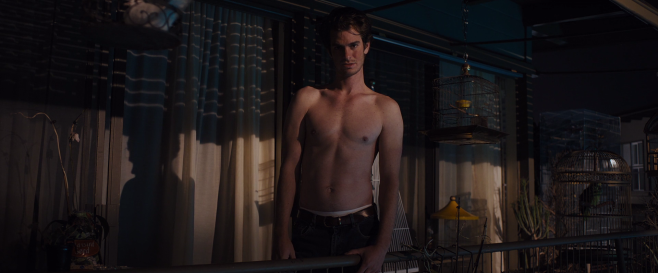

“NO ONE WILL EVER BE HAPPY HERE UNTIL ALL THE DOGS ARE DEAD.” On January 17th, 2019, I checked out Under the Silver Lake, David Robert Mitchell’s followup to his surprise hit horror film, It Follows. As the review says, I enjoyed it, but I didn’t have all that much to say. It’s fun, it puts you in a wacky headspace, yadda yadda yadda, I didn’t understand what happened but enjoyed it nonetheless. Current day Joey would’ve watched the film again a week later, but in the infancy of What’s Joey Been Watching?, I was more than content to watch and move on. A few months ago, I decided to watch Under the Silver Lake again, recalling how “fun” it was and wanting to unwind for the night with some easy viewing. Instead, I ended up realizing that Under the Silver Lake tricked me into thinking it’s a fun, confusing treasure hunt when in reality it’s a brilliant blend of provocative themes revolving around a hopelessly lost character who does not understand what he’s doing or why he’s doing it. I’ve watched it three more times since, and each viewing provides me with a more fleshed out and vivid portrait of Andrew Garfield’s character, Sam, and the fucked up city he lives in.

Under the Silver Lake is in part about conspiracy theories, so let’s start with one: Under the Silver Lake is such a scathing criticism of Hollywood/LA culture that it was refused a legitimate theatrical release and critics were forced to damn it with faint praise. It sits at a neutral yellow “60” out of 100 on Metacritic, and received an even worse score on Rotten Tomatoes. This is in spite of the fact that Under the Silver Lake is a dense, hilarious, and terrifying film that challenges the viewer to both scan every frame and to ignore all the superfluous details at the same time. While I don’t necessarily believe my own theory, I do think it’s heinous that so many critics wrote this movie off as a hollow comedy with too many plot threads that go nowhere when it’s so much more than that. If you have Amazon Prime, go watch it and come back, not only because it’s fantastic but because this post is written assuming you’ve not only seen it but seen it recently enough to remember every detail. I’m very aware there’s a possibility literally nobody reading this will fit that description, but if I dwell too long on that thought, I’ll drive myself mad. Who am I kidding, I was driven off my rocker the second I started trying to understand Under the Silver Lake.

I spent a bunch of time on Reddit following my first viewing, poring over remarkably dense posts trying to piece together the complicated secret codes hidden within the film. It revealed some fun easter eggs and references to real world locations, but it felt a little empty even at the time. Now I know why. These people clamoring desperately for some kind of hidden meaning within the mysteries of the Silver Lake are playing into exactly what David Robert Mitchell is satirizing. Sam is a character obsessed with finding hidden meaning in every moment of his life following a somewhat strange encounter with a beautiful woman (I guarantee Sam would never have gone on this escapade if she weren’t beautiful), and is genuinely worrying the few people in his life who actually care about his wellbeing. He’s looking for meaning where there is none, like all the Redditors out there who may be great at deciphering codes but aren’t so great at self-awareness. These frivolous secret messages function brilliantly as a way for the audience to relate to a character who, under closer examination, is an absolute piece of shit. It tricks you into employing the same twisted mindset Sam is so entrenched in, and makes the viewer complicit in Sam’s delusions. Mitchell has placed bells and whistles all throughout his film to purposely obfuscate the film’s deeper and darker implications that make you feel bad for ever sympathizing with Sam once you find out what Under the Silver Lake is actually trying to say. The character of Sam is desperate and foolish, and Mitchell wants you to feel the same.

I mentioned earlier that Sam doesn’t know why he’s doing what he’s doing, and I believe that to be true right up until he’s chained in the cave with the Homeless King. Yes, we’re skipping right to the end of the movie already. The cave scene is the culmination of every theme the film employs, and it will be addressed in relation to every single subject I will bring up in this analysis. When the Homeless King lets him go free, Sam finally understands what he’s spent the past few days doing. A couple offhand comments and one curiously mundane scene earlier in the film suddenly became imperative to understanding what it all really means. As much as I hate the trope of “it was all in his head”, I strongly believe that most of the events depicted in the film are either embellished to a comical degree or made up entirely. Rather than being a tired narrative copout, the decision to make many of Sam’s absurd encounters completely imagined gives the viewer a fascinating window into how he sees himself and how he subconsciously conjures up a world that gravitates around him.

What may be initially alienating about Under the Silver Lake is the fact that Sam’s motivation for unraveling this gargantuan conspiracy appears to be pretty weak. He meets a pretty girl named Sarah who moves out of his complex and disappears the day after they share an intimate moment and all of a sudden he endeavours to be the next Sherlock Holmes. I don’t blame you if you spent much of the movie asking why the hell he cares so much. One thing that is now abundantly clear to me is that Sam is not searching for Sarah herself, but more the idea of her. In his head, he has idealized and deified this girl for reasons even he doesn’t seem to understand, nor does he ever consider until the Homeless King forces him to.

What the Homeless King represents is Sam’s superego: His buried and neglected sense of humility, morality, and self-awareness. Even the Homeless King’s lines earlier in the movie reflect this: “Some people don’t realize this about themselves, but, uh, you… don’t have a good smell about you.” Sam has no inhibitions about following a surreal wild goose chase because his sense of reason is out of whack; he thinks the world, specifically the media, is designed for a mythical elite, and that this powerful group is operating directly under everyone’s nose. Ironically, he isn’t far off, but more on the plight of capitalism later.

Let’s now answer the question I posited before: Why is Sam doing all this; why is Sam so obsessive and unreasonable and chasing after some girl he just met? The reason is surprisingly simple, but the film does its best to obfuscate the answer from the audience just as Sam has shielded himself from this very same question. The reason Sam is on his fictitious quest is because he has lost any sense of identity following a breakup that has left him devastated and directionless.

At the party where he meets Sevence’s daughter, Sam speaks briefly with a girl he clearly has a history with.

It’s never outright stated, but the way they interact and the long, distant stare he directs at one of the billboards she’s featured on earlier in the film makes it obvious that they were in a relationship at some point before the film’s events begin. Their interaction is banal and borders on normal, which makes it stick out like a sore thumb in a movie that’s otherwise in a constant state of chaos and disaffecting bizarreness. For a fleeting moment, Sam is slammed back down to Earth and forced to face reality, something he hasn’t done for at least as long as we’ve been watching him. Their conversation is awkward and he appears shell shocked but for the first time, we see him trying to fit in; he’s trying to at the very least appear normal. He forces a smile, even, and wishes her and her fiancé congratulations on their engagement. In the scene earlier in the film when he calls the prostitute from Shooting Star Escorts, he goes on a rant about work: “Oh god, all I’m ever hearing is ‘what do I do for work’, or ‘how’s work,’ ‘where’s – where do you work,’ ‘work…work good?’ ‘You working hard?’” But when his ex asks him how work is at the party, he simply responds with “great” (I still can’t figure out where he could possibly work, but I guess the point is that we don’t know and it doesn’t matter one lick). Sam obviously cares what she thinks of him, and he’s suddenly aware that some of his antics are far outside the range of what can be considered normal. He shows a hint of self-awareness earlier in the movie when he’s explaining his Wheel of Fortune theory to The Actress, but that’s before he meets Comic Man (look, I’m just pulling these character names directly from the IMDb page, it’s not my fault they’re vague) and he starts to truly go off the rails. After the conversation with his ex, he goes right back to his absurd delusions, but this isolated instance of normalcy sets him up to understand and take to heart the Homeless King’s wise words at the end of the film.

As much as Sam grows by the end of the film, he is not a good person, and Under the Silver Lake never treats the audience like they should sympathize with him (relate, sure, but never sympathize). Yes, he’s mentally ill, but that doesn’t excuse his blatant misogyny and general asshole-ishness (see: Greenberg in Noah Baumbach’s film Greenberg). Let’s delve into the root of his misogyny and connect it back to some of the frequent themes throughout the film. One unmistakable recurring motif is dogs and barking – the film starts with a shot warning citizens of a mysterious dog killer on the loose in LA. Is there a literal dog killer? Who knows and who cares, the only important thing about the dog killer is how it relates to Sam and how he perceives women. His ex had a dog, that much is explicit, but what happened between Sam and his ex is never even hinted at, meaning we can only speculate as to why he seems to see women as canines. Which women he sees as dog-like may provide some clues, however. We see humans bark three different times: Once in a dream sequence where a strange man dressed like Sarah barks at him while eating a dead dog, once when he’s kneed in the balls in the women’s washroom, and once in a dream sequence where Sarah does her Marilyn Monroe-esque pool routine. These are all entirely different scenarios, so let’s try to reconcile them and perform an amateur psychoanalysis of Sam. The most obvious one to interpret is the bathroom scene, since it heavily implies that he sees women as pestering, overbearing, cruel, and even intimidating. The Sarah in the pool dream sequence is a little more complex, as I believe it shows that Sam sees women as if they’re sirens: They draw him in with sex appeal only to berate – or bark – at him when he actually starts to get close to them. The nightmare dog eating scene is the strangest as it isn’t even a woman barking at him, it’s a man dressed as a woman barking like a dog.

If I had to guess, I would say that this dream tells us Sam is skeptical of women and lacks any trust in them, and believes they will turn into something entirely different if he ever gets close to one.

Clearly Sam’s view of women is tainted and warped, but what the hell does this have to with dogs? Early on in the movie, we’re given a hint: During Sam’s first encounter with Sarah, she asks him what kind of dog he has. He responds, “My dog died recently.” It looks like Sam views his relationship with his ex like he would a relationship with a cherished pet, and this is explicit in the final Homeless King scene where Sam admits at last that he’s been keeping dog biscuits as a symbol of his continued affection for his ex, something he paradoxically refuses to acknowledge but can’t seem to ignore. A dog is also a creature known for being affectionate and loving regardless of whether you’re good or bad, rich or poor, etc., as long as you’re good to them. They’re simple animals, while women are a puzzle box that Sam isn’t willing to invest time into solving. That could be what ended his relationship in the first place. His revelation at the end is not that he needs to try harder, though. He knows that he needs to give up hope in a failed relationship and he must try to find meaning somewhere else, somewhere in the real world rather than in an imaginary hellscape of conspiracy.

But how do we know Sam is in a better place by the end of the movie? It looks like he’s the same sleazy loser he was in the beginning judging by his odd reaction to his own eviction following sex with his neighbour. Well, there are a couple of clues that suggest Sam understood the Homeless King and genuinely wishes to improve himself. First and most on the nose is the return of the opening shot: We look out at the LA streets from a café window vandalized with the words “BEWARE THE DOG KILLER” once again, but this time, the person trying to clean the graffitied warning seems to have made some progress; it’s starting to fade just as Sam’s delusions are.

The final scene of the movie is the most indicative of Sam’s change, as it sees him explicitly ignoring what he could easily have construed earlier as a hidden message. In this scene, he goes next door to sleep with the older woman with a rather vocal parrot we’ve seen throughout the film, and he finally asks her: “Hey, what is that bird saying?”, and for the first time, he takes “I don’t know” as an answer and doesn’t look any further. He goes outside to smoke and watches as his landlord officially kicks him out of his apartment – he’s finally found his peace. Sure, he’s homeless, alienated, and still entirely aimless, but he’s no longer tortured by his past; all he has is a bleak future.

Searching for optimism and forcing a smile while your life is still falling apart – isn’t that the LA experience in a nutshell? As fascinatingly broken as Sam is, the real pathetic loser of this movie is Los Angeles, California, a cesspool filled to the brim with washed up neverbodies and hopeful young talentlesses. Under the Silver Lake depicts LA as a place where dreams go to die but people’s need to chase them thrive, creating an endless cycle of confidence and disappointment. The bizarre spectacle at about 43 minutes is the most obvious mocking of LA culture and mindset, featuring colourfully adorned women lining up, headshots in hand, outside some creepy guy’s garage touting a cardboard sign: “MOVIE AUDITIONS”.

Disasterpeace’s score paired with the whimsical cinematography of the scene feels like it’s purposely skewering La La Land, a film that glamorizes the LA struggle through flashy, colourful musical numbers. As much as I love La La Land, I find Under the Silver Lake to be a far more honest and frank depiction of how aspirations are truly treated in Hollywood. Since I don’t live in LA, I’m not exactly in a position to be accusing one movie or the other of being disingenuous, but from what I’ve heard and what I’ve seen from my limited experience working in the entertainment industry, it can be quite a bit more soul crushing than La La Land makes it seem. Being a struggling artist is possibly the most depressing profession, as it requires a perpetual feeling of hope and a purposeful ignorance of the likelihood that you’ll never make it. LA is the world capital of struggling artists, making it one of the most depressing places on Earth.

That’s without even mentioning the rampant homelessness issues, another recurring theme throughout Under the Silver Lake that aims its sights at the flawed mentality of the LA populace. I’ve already discussed the Homeless King as an extension of Sam himself, but I want to look at this strange crowned hobo as a representation of Sam’s overt classism and a larger metaphor for the capitalist mindset. When the true message of “Turning Teeth” reveals itself to Sam, he’s ecstatic and doesn’t waste a second before booking it to the planetarium. He rubs Dean’s head and waits under Newton, eagerly awaiting what the next step of his journey could mean for him. As soon as he sees the Homeless King, though, he becomes apprehensive and suspicious.

Of course, the Homeless King is very strange and surely suspicious, but Sam has proven time and time again that he has no qualms about meeting strange people; he makes it pretty obvious that the only reason he’s so reluctant is due to the fact that the Homeless King is, well, homeless, and Sam looks down on him. Later on, Sam is walking along the reservoir with Millicent Sevence and says “I know it’s not okay for me to say this but I fucking hate the homeless. Everybody says we need to take care of them but I think they’re fucking bullies. Poltergeists.” He continues on a brief rant about how they’re jealous of the people they have to watch go about their lives, and they harass people out of spite. Millicent replies, “Why not just give them a dollar next time?”

Sam’s disdain for the homeless population reflects what I believe to be the sentiment of many people in our part of the world, and elucidates one of the many cracks in the capitalist system. Millicent’s quick feedback is advocating for a world where sympathy for the less fortunate is not treated as treachery. Yes, I believe that David Robert Mitchell is making a deliberate statement about socialism and the welfare state. The endless competitiveness of capitalism minimizes sympathy to those without our own advantages and encourages us to see our own value as represented by our wealth. Sam is merely hours from ending up homeless himself, and yet he uses some of that precious time to cuss out the very thing he will soon become. It’s rather similar to what Bong Joon-Ho’s Parasite satirizes: While the upper class is most definitely filled with privileged and oblivious elite capitalists, the lower class must break away from the pitfalls of the economic system and help each other rather than stepping on the heads of those immediately below them. The Kim family in Parasite has only barely become acquainted with the upper class lifestyle when they encounter a desperate family much like their own used to be, and instead of aiding them, they perpetuate the vindictive cycle of capitalism. Sam is in a similar yet opposite situation: He’s a lower-middle class man adjacent to homelessness but finds no sympathy within himself for those below him, nor does he find any irony in his actions. That is, of course, until that final encounter with the Homeless King. This scene serves as a reconciliation of Sam’s classism, as he begins to appreciate what the Homeless King has to offer and understand his wisdom. In the film’s final scene, Sam watches from a distance as he’s evicted from his apartment. Instead of feeling hopeless, Sam feels at peace, having finally come to terms with his failed relationship and internalizing a respect for the homeless population that he is about to join the ranks of.

Over the course of the film, we see Sam gain more and more disdain for not only the less powerful but for the all-powerful gods of LA: celebrities. At the end of his encounter with The Songwriter, Sam annihilates the elderly man’s brains with Kurt Cobain’s guitar, leaving a red mess where a head used to be. It’s a shocking moment of body horror in an otherwise horror-light movie, standing out even among other ludicrously constructed scenes. This is an important moment for Sam, as it adds to the narrative of Sam being trapped in his past and displays his staunch disapproval of anything that may force him to move on. In the scene where he has sex with the actress while watching the breaking news regarding Sevence, we are introduced to two influences from Sam’s past: Kurt Cobain himself, and a specific issue of Playboy featuring a woman underwater on the cover. Later on, both of these influences are bastardized – The Songwriter claims to have written Smells Like Teen Spirit, ruining Sam’s perception of one of his idols, and Millicent Sevence is killed in the reservoir in such a way that she explicitly mimics the Playboy cover, but this time with a whole lot more blood. The Songwriter incident as a metaphor is more easily picked apart, since it depicts Sam using Cobain’s guitar to obliterate The Songwriter’s head much like Cobain did to himself with a shotgun.

It shows that Sam is under the impression that his entire life has been a lie, including the people he idolized, and he has lost any sense of the innocence he wants so badly to preserve. He uses a Nintendo Power Magazine and a cereal box toy to solve a clue later; clearly Sam is trying to maintain a childlike sense of innocence when LA makes that fundamentally impossible.

The Playboy issue is used as a similar metaphor, as Sam uses the magazine to reminisce about a time when sexual gratification was new and exciting unlike the distracted, only somewhat enthusiastic sex he was having moments earlier. When Millicent is shot, his cherished sexual memory is tainted and warped, forcing him to accept that he isn’t a naive child anymore.

I thought maybe there would be some parallels between the Playboy cover girl, Janet Wolf, and Kurt Cobain, but alas, Janet Wolf is a mystery model. I paid $8 to get access to all of the Playboy archives and pored over the issue for a long time looking for any more information on her, but alas, she was forgotten after July of 1970. If I wanted to tie everything together by potentially reading way too much into things, I could say that the Playboy cover relates to the album cover for Nirvana’s Nevermind, with the former representing Sam’s sexual idealism and Nevermind representing his childlike sense of wonder, both of which are repressed in the form of being underwater, which all connects to the title of the movie.

Am I going insane or does that actually make a little bit of sense? I may just be going crazy. I feel like Sam. Was I wrong? Did David Robert Mitchell want me to feel this way, or did he want to make fun of me for wanting everything to make sense?

My understanding of Under the Silver Lake is never going to be complete. If I wanted to, I could delve into how the film uses our idealistic and rose-tinted perception of “old Hollywood” to satirize LA culture both past and present, or I could write a thousand words on coyotes. I might be able to compose an entirely separate essay on the various Harvey Weinstein analogues presented in the film, and write more about how the film calls out the blind celebrity worship that isn’t even exclusive to LA. But I have to stop somewhere, otherwise I’ll drive myself insane and never put out any more content. Under the Silver Lake is the kind of masterpiece that only comes around once in a blue moon, and yet I completely understand if you watched it and absolutely hated it. The main character is a total prick, and his journey is, on the surface, nonsensical and downright stupid at times. If you’re willing to peek under the hood, though, you may find the meaning you seek. “For now the answers remain hidden, deep below the surface…VOEFS UIF TJMWFS MBLF.”