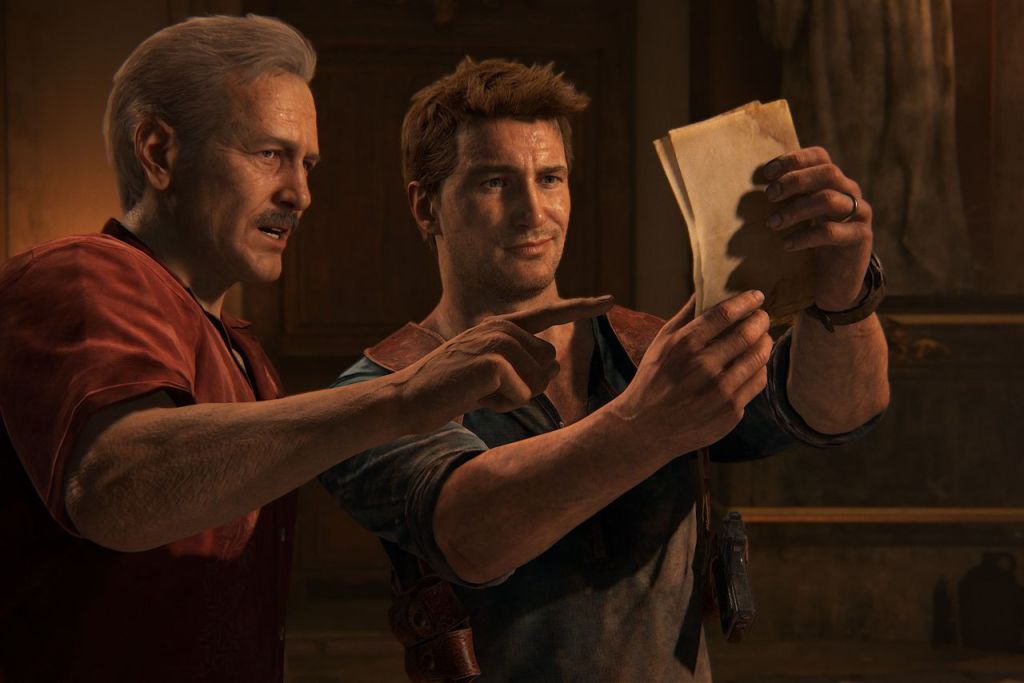

Nobody wants a forced retirement. We all want to finish our careers on a high note at a ripe age when we still have the time to do the things we want to do while making sure not to run out of retirement money. Unfortunately for Nathan Drake – hero of the Uncharted video game franchise – and Indiana Jones, they are not real, tax-paying people, and they are therefore not afforded the luxury of choice. If a developer or studio wants to bring them back for one last job, they are to oblige, so it is written in their contractual agreements as fictional characters. Can you imagine how Jason Voorhees feels, dragged back from the depths of cinematic (and critical) (and literal) hell again and again? Sometimes one last job feels destined, like the stars aligned to provide the perfect send-off; sometimes it feels drably inevitable based on the previous iteration’s box office performance. It should be obvious which categories Nathan Drake and Indiana Jones fit into.

I will afford Indy a few minor defences when pitted against its vastly superior copycat. First is the amount of time spent with the character: the total runtime of every Indiana Jones movie is 10.6 hours, while howlongtobeat.com puts completion of all the Uncharted games – not even including spinoffs – at 42.5 hours. Is this a fair, equal comparison? Absolutely not, it’s likely that more than half of those 42.5 hours are made up of shooting goons while Nathan is yelling or wise-cracking rather than progressing his story. But Nathan feels like a character that has had more time to develop an arc over the course of his four games simply due to the fact that the amount of time we spend with him necessitates it.

The other defence is intention: Indiana Jones movies know what they are, and they aren’t much. I mean no disrespect to the franchise, but they’ve always been rather shallow and lacking in meaningful character reflection or development. Indy has always been a too-old-for-this-shit (in spirit, anyway), no nonsense daredevil with a heart of gold and a penchant for Nazi killing, and I wouldn’t say that I expect any film in the franchise to subvert that, but I would welcome, well…anything that changes him in any substantive way. It’s the glaring lack of a point or punctuation that defines Indy 5, and there’s nothing I can do to defend that.

Why does the adventurer adventure? This question alone is more of a theme than anything Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny attempts to employ. The fourth and decidedly, emphatically final mainline Uncharted game, Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End, takes an introspective look at why Nathan Drake insists on putting his life in danger and the ways in which it affects the people he loves. This isn’t simply a backdrop to present exciting gunfights and impossible setpieces, it’s an earnest thesis that takes centre stage arguably more than its (also excellent) gameplay. It’s a story about taking inventory of your life’s achievements and figuring out whether it’s enough to be content. It’s a story about willing naïveté and how we trick ourselves into believing what we want to believe. It’s a final chapter that surrounds itself with the appropriately nuanced themes of being a final chapter. It is under no obligation to set itself up for a sequel, it has no reservations about providing a true epilogue, and it soundly completes every arc it sets up. Uncharted wants to end, and I mean that in the most interesting way possible, like it’s the last season of a great TV show going out on its own terms.

Dial of Destiny is a weird point of comparison for Uncharted 4 since despite the fact that the Uncharted games are unabashedly a near copy/paste of Indiana Jones in concept, their approaches to ending their franchises couldn’t possibly be more different. In all honesty, it’s difficult to pit the two against each other since one does everything it can to wrap up its franchise with an emotional, triumphant conclusion while the other just…sits there, waiting to end when the script says so. Indy’s arc is confined to approximately two lines: one in which he mourns his son and laments not stopping him from going to war, the other in which he lets go of the past and accepts his present. What steps were taken in between these moments to achieve this supposed growth is a mystery to me since not a single other second is dedicated to this theme (let’s be honest here, the time travel shenanigans have nothing to do with Indy’s supposed arc unless you force it to). No other moment, in fact, is dedicated to any kind of theme at all. It’s a movie that comes and goes without attempting a single new thought or idea; a baffling conclusion that feels as much like a conclusion as its predecessors, the only difference being that Harrison Ford is 81 and therefore it’s effectively rather difficult to make a direct sequel.

And therein lies the issue: of course, this is by design. The studio didn’t want a conclusion because if they definitively complete the quintology, what happens if they want to continue? If Dial of Destiny made $2 billion, they’d be forced to make another and another and another! Create the IndyCU! And of course you read this – and I write this – knowing full well that Dial of Destiny may go down as the biggest box office flop in cinematic history. Sigh. Studios are learning that nothing is a safe bet, not even Marvel movies nowadays and it’s going to send them scrambling.

What does the last Marvel movie look like? I’ll tell you what it won’t look like: Uncharted 4. No major franchise will end on that sweet, timely retirement that keeps people talking about how fondly they remember it forever and ever since there’s nothing new that could tarnish its memory. Franchises will end when they’re put down, and even then they’ll often just be revived again a few years later once everyone’s forgotten (see: Transformers rebooting itself in the Bumblebee universe after The Last Knight underperforms, see: DC rebooting itself after nearly everything lately underperforms, see: The Dark Universe, thrown in the trash nearly the second it was born giving way to…a standalone artsy thriller about abuse? The Invisible Man is an odd case). This, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, is what the end of a franchise looks like: a simplistic, formulaic, undemanding, serviceable, infuriatingly safe movie that does nothing to culminate and just enough to set itself up for the possible future (Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s character would feel like prime torch-passing material if they allowed her more personality). The last Marvel movie won’t look like Endgame, a phenomenal conclusion to the arcs of the original Avengers who dominated the box office like no film ever has. It will look like Ant-Man: Quantumania, a transitional nothingburger. It will look like Secret Invasion. It may even look like Venom: Let There Be Carnage. It will be the nail in the coffin, not the neatly tied bow. The end will look like the middle because it was never meant to end.

Movies – hell, nearly all art – has capital as its prime motivator. And so art will be abandoned if it no longer makes money. That is what we are seeing time and time again these days with movies and TV shows being removed from streaming so the platforms don’t have to pay for the rights. An Emmy nominated show is currently lost to the ether, unable to be seen by the general public without the (extremely ethical and underutilized) use of piracy. Bob Iger/David Zaslav/Tim Cook/literally any CEO in charge of anything creative does not care about art. They do not care about the artist. They are their bottom line, and they are the pleasure of their shareholders. So nothing will end naturally or satisfyingly, it will end well before or well after it was meant to. Netflix’s reputation as the streaming giant that won’t let anything go past a second season will continue and Max will strike from existence whatever shows and films they’d like because that’s what the CEO says will accumulate the most amount of revenue. The art you love is just business, a means to an end that will never be reached as long as money still exists that they don’t have.

Oh. oh no.

I just wanted to talk about Indiana Jones and the Uncharted series, where did it all go wrong? Bleak capitalist cynicism was never my intention, I swear! My Cate Blanchett Double Feature didn’t have enough of a point and now this post makes too much of a point! Whatever, I said what I said, capitalism is ruining movies like it always has and always will. It’s also ruining my job, which is now in extreme jeopardy due to the greed of the execs forcing a strike that has shut down both shows I work on. I’m gonna go ahead and guess that that’s why I accidentally veered towards some vitriolic capitalist hatred here. What I really want to highlight, to end on a positive note, is the excellence of Uncharted 4 and the beautiful themes it employs to finish its saga in the most gratifying way possible. Dial of Destiny had the perfect opportunity to at least try to keep up with the franchise that was so blatantly inspired by its predecessors and yet it almost feels like they went out of their way not to. Making something serviceable over and over until the end of time is easy. A work of greatness is hard, but just one can last forever.

…Unless it’s removed from streaming.

Joey! You are a great writer! I love the way you place your words so creatively! …already looking forward to your next post!

LikeLike